Factors and Dates

Learning Outcomes

- Use functions from the {forcats} package to manipulate factors in R.

- Describe the difference between a factor and a string.

- Convert between strings and factors.

- Reorder and rename factors.

- Change how character strings are handled in a data frame.

- Manipulate dates and times using the

lubridatepackage.- Use lubridate to parse different date formats.

- create date objects from multiple inputs.

- calculate intervals and durations between dates and times.

Factors: where they fit in

R has a special data class, called factor, to deal with categorical data that you may encounter when creating plots or doing statistical analyses. Factors are very useful and actually contribute to making R particularly well suited to working with data. So we are going to spend a little time introducing them.

Factors represent categorical data. They are stored as integers associated with labels and they can be ordered or unordered. While factors look (and often behave) like character vectors, they are actually treated as integer vectors by R. So you need to be very careful when treating them as strings.

Factors are the variable type that useRs love to hate. It is how we store truly

categorical information in R. The values a factor can take on are called the

levels. For example, the levels of the factor continent in Gapminder are

are “Africa”, “Americas”, etc. and this is what’s usually presented to your

eyeballs by R. In general, the levels are friendly human-readable character

strings, like “male/female” and “control/treated”.

Factors are particularly useful when making plots or running statistical models.

Unfortunately, they can also be very tricky to work with, because they are

secretly numbers behind the scenes. Working with factors in base R can lead to

errors that are almost impossible for human analysts to catch, but there is a

tidyverse package that makes it much easier to work with factors, and prevents

many common mistakes. It is called forcats (an anagram of the word “factors”

and also because it is a package for working with categorical

variables).

The forcats package

forcats is a core package in the tidyverse. It is installed via

install.packages("tidyverse") and attached via library(tidyverse). You can

always load it individually via library(forcats). Main functions start with

fct_. There really is no coherent family of base functions that forcats

replaces – that’s why it’s such a welcome addition.

Let’s load the forcats package so we can use the functions it comes with

library(tidyverse)

library(forcats)

And let’s load the data we’ll be using today, gapminder

library(gapminder)

Creating a factor:

Once created, factors can only contain a pre-defined set of values, known as levels. By default, base R always sorts levels in alphabetical order. For instance, if you have a factor with 2 levels:

factor(c("sad", "happy", "happy", "sad"))

## [1] sad happy happy sad

## Levels: happy sad

R will assign 1 to the level "happy" and 2 to the level "sad"

(because h comes before s in the alphabet, even though the first element in

this vector is"sad").

In R’s memory, factors are represented by integers (1, 2), but are more

informative than integers because factors are self describing: "happy",

"sad" is more descriptive than 1, and 2. Which one is “sad”? You

wouldn’t be able to tell just from the integer data. Factors, on the other hand,

have this information built in. It is particularly helpful when there are many

levels.

However, the default ordering of levels in base R is less than ideal, because it depends on the language you have set for your R session, and can lead to un-reproducble code.

In the forcats package, there is a function that makes a factor but creates

the levels in the order they appear.

feeling <- as_factor(c("sad", "happy", "happy", "sad"))

feeling

## [1] sad happy happy sad

## Levels: sad happy

You can see the levels and their order by using the function levels() and you

can find

the number of levels using nlevels():

levels(feeling)

## [1] "sad" "happy"

nlevels(feeling)

## [1] 2

Let’s move onto our data frame now to investigate the continent factor.

Factor inspection

Get to know your factor before you start touching it! It’s polite. Let’s use

gapminder$continent as our example.

str(gapminder$continent)

## Factor w/ 5 levels "Africa","Americas",..: 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 ...

levels(gapminder$continent)

## [1] "Africa" "Americas" "Asia" "Europe" "Oceania"

nlevels(gapminder$continent)

## [1] 5

class(gapminder$continent)

## [1] "factor"

To get a frequency table as a tibble, from a tibble, use dplyr::count(). To

get similar from a free-range factor, use forcats::fct_count().

gapminder %>%

count(continent)

## # A tibble: 5 x 2

## continent n

## * <fct> <int>

## 1 Africa 624

## 2 Americas 300

## 3 Asia 396

## 4 Europe 360

## 5 Oceania 24

fct_count(gapminder$continent)

## # A tibble: 5 x 2

## f n

## <fct> <int>

## 1 Africa 624

## 2 Americas 300

## 3 Asia 396

## 4 Europe 360

## 5 Oceania 24

This may feel familiar - you’ve worked with factors before!

reordering factor levels

Sometimes, the order of the factors does not matter, other times you might want to specify the order because it is meaningful (e.g., “low”, “medium”, “high”), it improves your visualization, or it is required by a particular type of analysis.

By default, factor levels are ordered alphabetically. Which might as well be random, when you think about it! It is preferable to order the levels according to some principle:

- Frequency. Make the most common level the first and so on.

- Another variable. Order factor levels according to a summary statistic for another variable. Example: order Gapminder countries by life expectancy.

In forcats, one way to reorder our levels in the continent vector would be

manually, using fct_relevel:

levels(gapminder$continent) # current order

## [1] "Africa" "Americas" "Asia" "Europe" "Oceania"

# Reorder by population:

gapminder <- gapminder %>%

mutate(continent_reordered = fct_relevel(continent,

"Asia",

"Africa",

"Americas",

"Europe",

"Oceania"))

levels(gapminder$continent_reordered) # after re-ordering

## [1] "Asia" "Africa" "Americas" "Europe" "Oceania"

The fct_relevel function allows you to move any number of levels to any

location. If you re-specify the entire list of levels, it will re-order the

whole list. But, if you just specify one level (like we did here) that level

gets moved to the front of the list.

# Reorder by population:

gapminder <- gapminder %>%

mutate(continent_reordered2 = fct_relevel(continent, "Asia"))

levels(gapminder$continent_reordered2) # after re-ordering

## [1] "Asia" "Africa" "Americas" "Europe" "Oceania"

Another way to re-order your factor levels is by frequency, so the most common

factor levels come first, and the less common come later. (This is often useful

for plotting!) In this case, it is the frequency of how often each level occurs

in the variable, as seen in fct_count(gapminder$continent)

levels(gapminder$continent)

## [1] "Africa" "Americas" "Asia" "Europe" "Oceania"

gapminder <- gapminder %>%

mutate(continent_infreq = fct_infreq(continent, ordered = TRUE))

levels(gapminder$continent_infreq) # after re-ordering

## [1] "Africa" "Asia" "Europe" "Americas" "Oceania"

What if we want to order the continent factor based on the values of another

varialbe? This other variable is usually quantitative and you will order the

factor according to a grouped summary. The factor is the grouping variable and

the default summarizing function is median() but you can specify something

else.

head(levels(gapminder$country))

## [1] "Afghanistan" "Albania" "Algeria" "Angola" "Argentina"

## [6] "Australia"

## order countries by median life expectancy

gapminder <- gapminder %>%

mutate(country_med_lifexp = fct_reorder(country, lifeExp))

head(levels(gapminder$country_med_lifexp))

## [1] "Sierra Leone" "Guinea-Bissau" "Afghanistan" "Angola"

## [5] "Somalia" "Guinea"

## order according to max population instead of median life expectancy

gapminder <- gapminder %>%

mutate(country_min_pop = fct_reorder(country, pop, .fun = max))

head(levels(gapminder$country_min_pop))

## [1] "Sao Tome and Principe" "Iceland" "Djibouti"

## [4] "Equatorial Guinea" "Bahrain" "Comoros"

## backwards!

gapminder <- gapminder %>%

mutate(country_min_pop = fct_reorder(country, pop, .fun = max, .desc = TRUE))

head(levels(gapminder$country_min_pop))

## [1] "China" "India" "United States" "Indonesia"

## [5] "Brazil" "Pakistan"

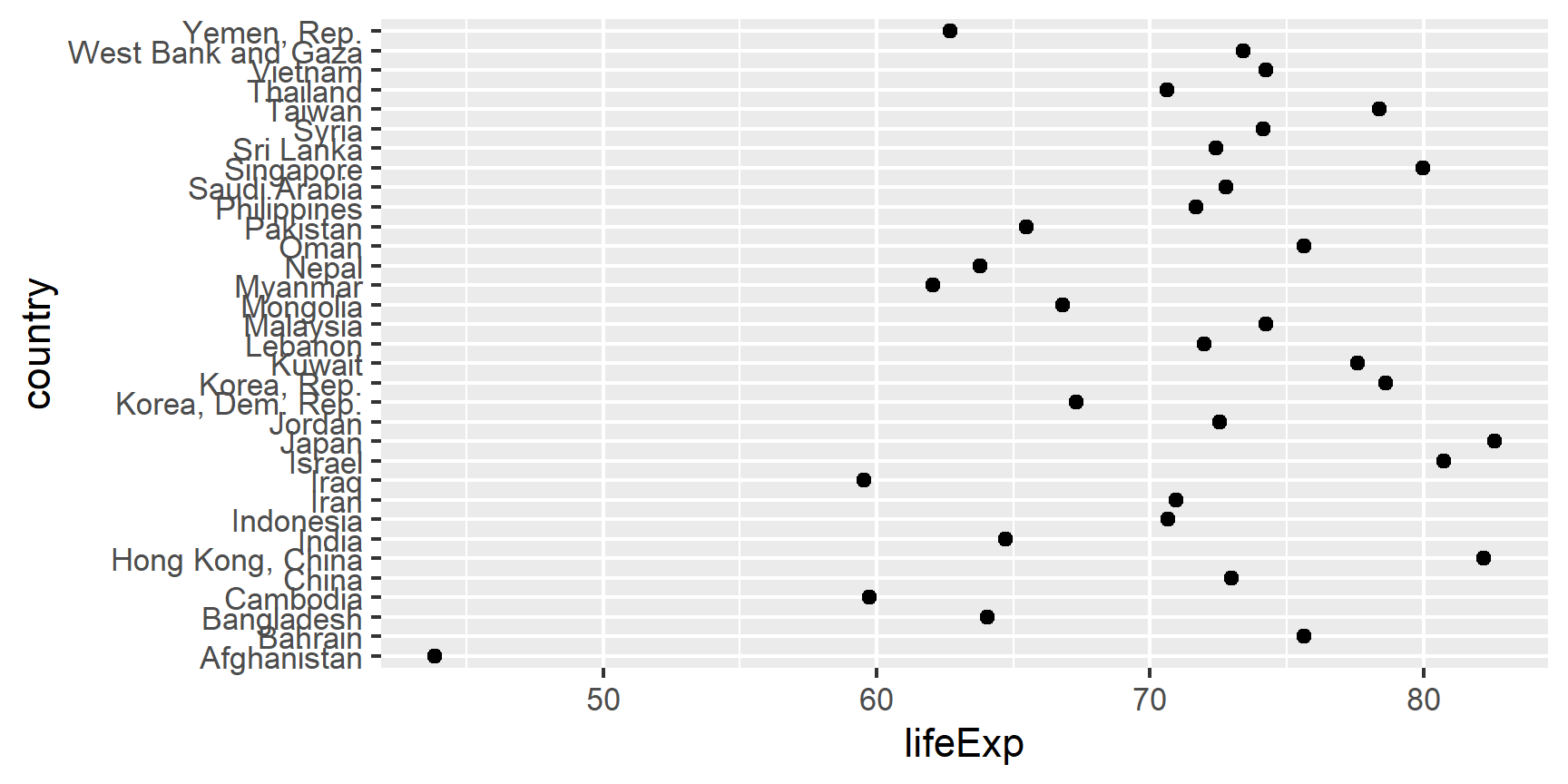

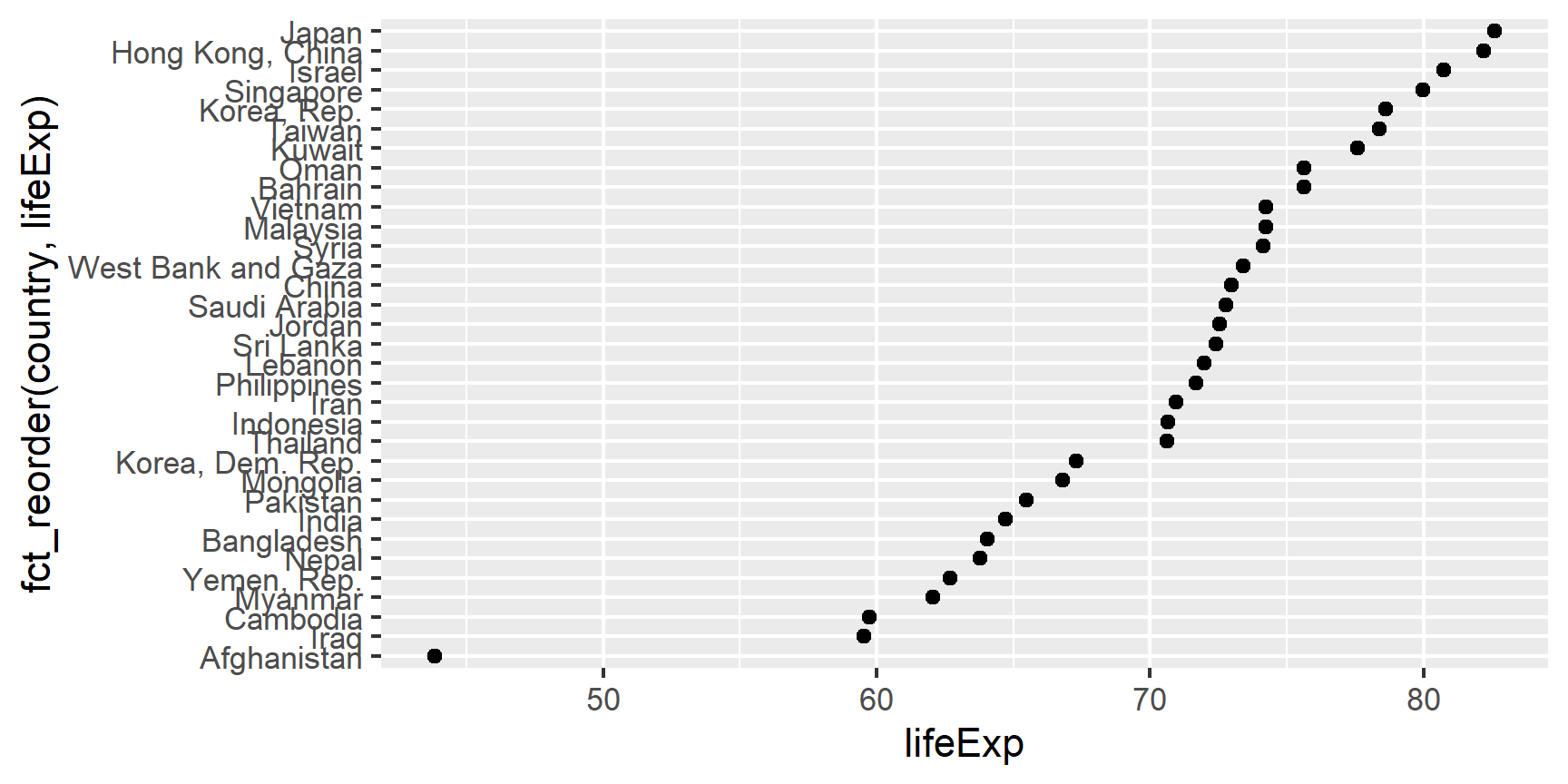

Example of why we reorder factor levels: often makes plots much better! When a factor is mapped to x or y, it should almost always be reordered by the quantitative variable you are mapping to the other one.

Compare the interpretability of these two plots of life expectancy in Asian

countries in 2007. The only difference is the order of the country factor.

Which one do you find easier to learn from?

gap_asia_2007 <- gapminder %>% filter(year == 2007, continent == "Asia")

ggplot(gap_asia_2007, aes(x = lifeExp, y = country)) + geom_point()

ggplot(gap_asia_2007, aes(x = lifeExp, y = fct_reorder(country, lifeExp))) +

geom_point()

Use fct_reorder2() when you have a line chart of a quantitative x against

another quantitative y and your factor provides the color. This way the legend

appears in some order as the data! Contrast the legend on the left with the one

on the right.

renaming factor levels

forcats makes easy to rename factor levels. Let’s say we made a mistake and

need to recode “Oceania” to “Australia”. We’d use the fct_recode function to

do this.

levels(gapminder$continent)

## [1] "Africa" "Americas" "Asia" "Europe" "Oceania"

gapminder <- gapminder %>%

mutate(continent_recode = fct_recode(continent, Australia = "Oceania"))

levels(gapminder$continent_recode)

## [1] "Africa" "Americas" "Asia" "Europe" "Australia"

There are many other forcat packages for very specific uses - like making an

“other” factor for rare occurrences with fct_lump(). Explore the cheatsheet so

you know what is available!

The lubridate Package

The lubridate package has many functions to simplify working with dates and times. The lubridate package does not come loaded as part of the tidyverse so you need to load it separately. Install the package if needed (using the console).

library(tidyverse)

library(lubridate)

Three main classes for date/time data

Datefor just the date.POSIXctfor both the date and the time (with Time Zone).- “POSIXct” stands for “Portable Operating System Interface - Calendar Time”. It is a part of a standardized system (based on UNIX) of representing time across many computing computing platforms.

hmsfrom thehmsR package for just the time. “hms” stands for “hours, minutes, and seconds.”

today() gives the current date in the Date class.

today()

## [1] "2021-03-27"

class(today())

## [1] "Date"

now() gives the current date-time in the POSIXct class.

now()

## [1] "2021-03-27 17:06:46 MST"

class(now())

## [1] "POSIXct" "POSIXt"

Parsing Dates and Times Using lubridate

lubridate has many "helper" functions which parse dates/times more automatically. - The helper *function name specifies the order of the components*: year, month, day, hours, minutes, and seconds. The help page forymd` shows multiple functions to parse dates with different sequences of

year, month and day,

Only the order of year, month, and day matters

ymd(c("2011/01-10", "2011-01/10", "20110110"))

## [1] "2011-01-10" "2011-01-10" "2011-01-10"

mdy(c("01/10/2011", "01 adsl; 10 df 2011", "January 10, 2011"))

## [1] "2011-01-10" "2011-01-10" "2011-01-10"

For times, only the order of hours, minutes, and seconds matter

hms(c("10:40:10", "10 40 10"))

## [1] "10H 40M 10S" "10H 40M 10S"

Let’s parse the following date-times.

t1 <- "05/26/2004 UTC 11:11:11.444"

t2 <- "26 2004 05 UTC 11/11/11.444"

mdy_hms(t1)

## [1] "2004-05-26 11:11:11 UTC"

## No dym_hms() function is defined, so need to use parse_datetime()

parse_date_time(t2, "d y m H M S")

## [1] "2004-05-26 11:11:11 UTC"

Now let’s use the appropriate lubridate function to parse the following dates:

d1 <- "January 1, 2010"

d2 <- "2015-Mar-07"

d3 <- "06-Jun-2017"

d4 <- c("August 19 (2015)", "July 1 (2015)")

d5 <- "12/30/14" # Dec 30, 2014

mdy(d1)

## [1] "2010-01-01"

ymd(d2)

## [1] "2015-03-07"

dmy(d3)

## [1] "2017-06-06"

mdy(d4)

## [1] "2015-08-19" "2015-07-01"

mdy(d5)

## [1] "2014-12-30"

Creating Date-time values from individual components

Use make_date() or make_datetime() to create dates and date-times if you

have a vector of years, months, days, hours, minutes, or seconds.

make_date(year = 1981, month = 6, day = 25)

## [1] "1981-06-25"

make_datetime(year = 1972, month = 2, day = 22, hour = 10, min = 9, sec = 01)

## [1] "1972-02-22 10:09:01 UTC"

You can see variables for the year, month, day, hour, and minute of the scheduled departure time with nycflights13 example:

library(nycflights13)

data("flights")

flights <- flights %>%

mutate(datetime = make_datetime(year = year,

month = month,

day = day,

hour = hour,

min = minute))

select(flights, datetime)

## # A tibble: 336,776 x 1

## datetime

## <dttm>

## 1 2013-01-01 05:15:00

## 2 2013-01-01 05:29:00

## 3 2013-01-01 05:40:00

## 4 2013-01-01 05:45:00

## 5 2013-01-01 06:00:00

## 6 2013-01-01 05:58:00

## 7 2013-01-01 06:00:00

## 8 2013-01-01 06:00:00

## 9 2013-01-01 06:00:00

## 10 2013-01-01 06:00:00

## # ... with 336,766 more rows

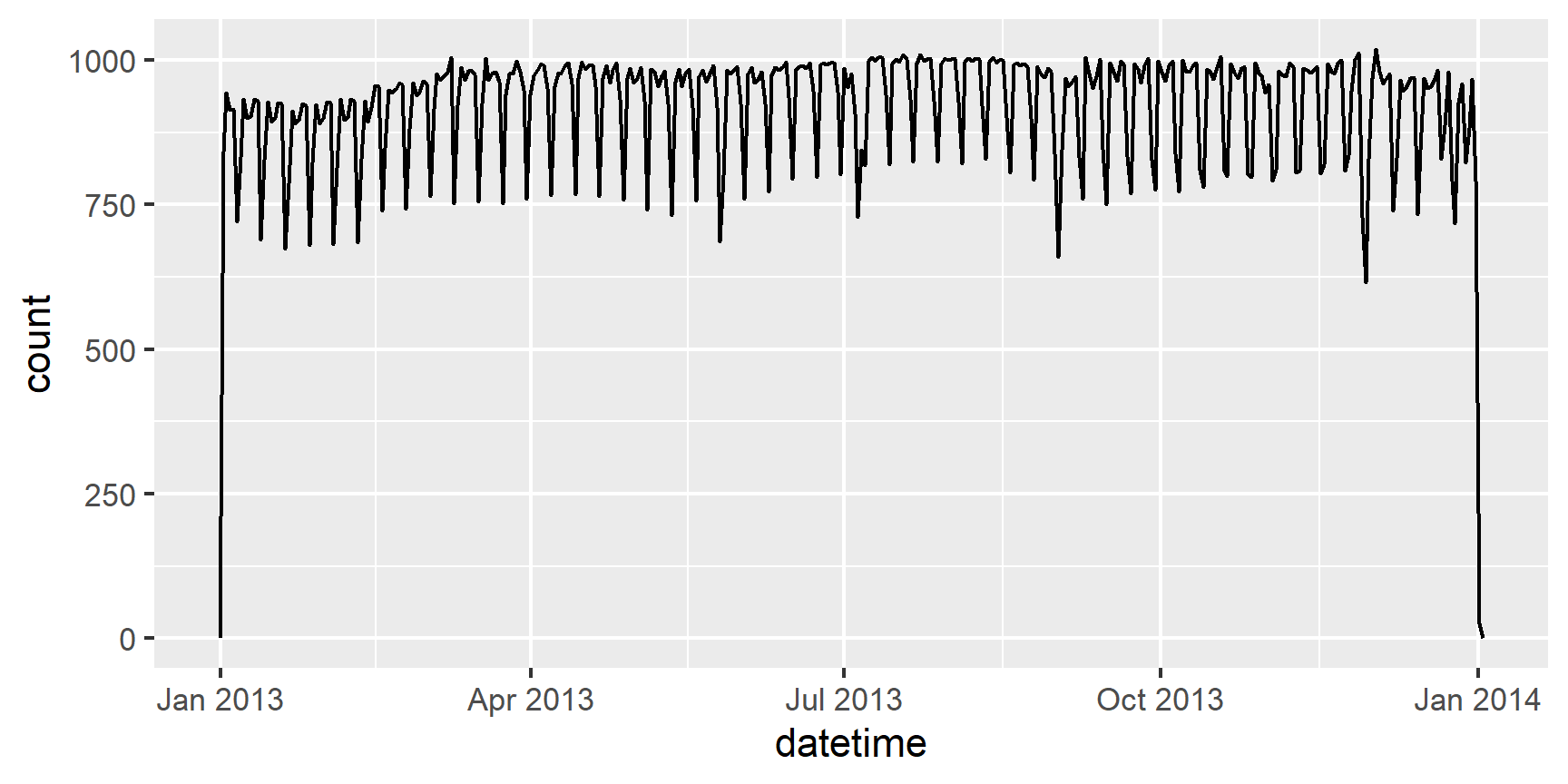

Having it in the date-time format makes it easier to plot.

ggplot(flights, aes(x = datetime)) +

geom_freqpoly(bins = 365)

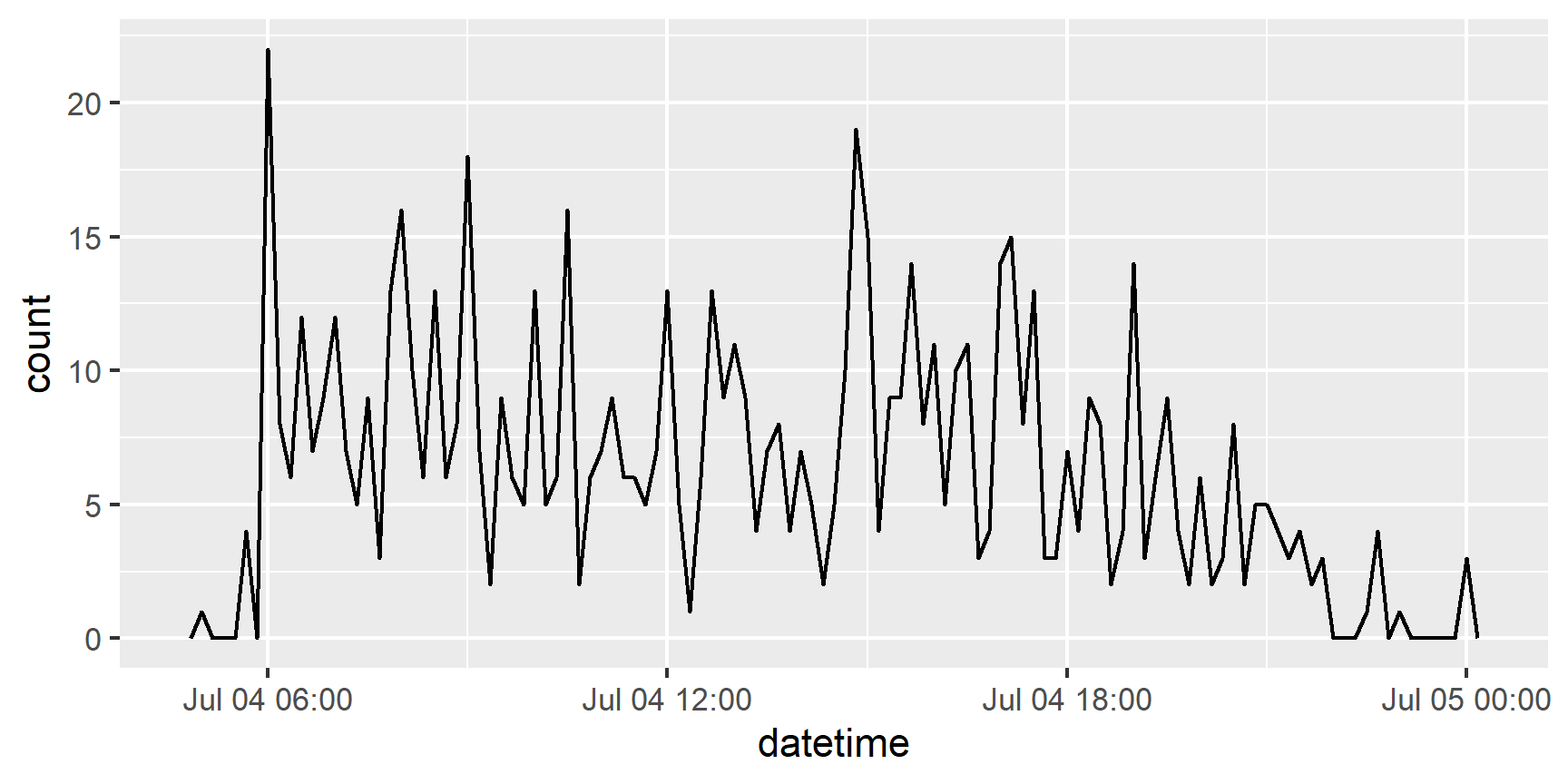

It also makes it easier to filter by date usingas_date() and ymd

flights %>%

filter(as_date(datetime) == ymd(20130704)) %>%

ggplot(aes(x = datetime)) +

geom_freqpoly(binwidth = 600)

Extracting Components of a date-time

To extract the component of a date-time, use one of the following:

year()extracts the yearmonth()extracts the monthweek()extracts the weekmday()extracts the day of the month (1, 2, 3, …)wday()extracts the day of the week (Saturday, Sunday, Monday …)yday()extracts the day of the year (1, 2, 3, …)hour()extracts the hourminute()extract the minutesecond()extracts the second

ddat <- mdy_hms("01/02/1970 03:51:44")

ddat

## [1] "1970-01-02 03:51:44 UTC"

year(ddat)

## [1] 1970

month(ddat, label = TRUE)

## [1] Jan

## 12 Levels: Jan < Feb < Mar < Apr < May < Jun < Jul < Aug < Sep < ... < Dec

week(ddat)

## [1] 1

mday(ddat)

## [1] 2

wday(ddat, label = TRUE)

## [1] Fri

## Levels: Sun < Mon < Tue < Wed < Thu < Fri < Sat

yday(ddat)

## [1] 2

hour(ddat)

## [1] 3

minute(ddat)

## [1] 51

second(ddat)

## [1] 44

Doing Math with Time

Humans manipulate “clock time” with the use of policies such as Daylight

Savings Time which creates

irregularities in the “physical time”. lubridate provides three classes of

time spans to facilitate math with dates and date-times.

+ Periods: track changes in “clock time”, and ignore irregularities in

“physical time”.

+ Durations: track the passage of “physical time”, which deviates from

“clock time” when irregularities occur.

+ Intervals: represent specific spans of the timeline, bounded by start

and end date-times. We won’t cover this in this lesson, but you can learn

more with ?interval-class

Periods

Make a period with the name of a time unit pluralized, e.g.

p <- months(3) + days(12)

p

## [1] "3m 12d 0H 0M 0S"

str(p)

## Formal class 'Period' [package "lubridate"] with 6 slots

## ..@ .Data : num 0

## ..@ year : num 0

## ..@ month : num 3

## ..@ day : num 12

## ..@ hour : num 0

## ..@ minute: num 0

You can read more about periods with

help("Period-class")

Durations

Durations are stored as seconds, the only time unit with a consistent length.

Add or subtract durations to model physical processes, like travel or

lifespan. You can create durations from years with dyears(), from days with

ddays(), etc…

dyears(1)

## [1] "31557600s (~1 years)"

ddays(1)

## [1] "86400s (~1 days)"

dhours(1)

## [1] "3600s (~1 hours)"

You can read about durations using

help("Duration-class")

You can also use duration(quantity, units = ...) to create a duration or

as.duration() to coerce an object to a duration. Example: We can find out the

exact age for the first single released by K-pop legends,

BTS using durations

d1 <- mdy("June 13, 2013")

d2 <- today()

str(d1)

## Date[1:1], format: "2013-06-13"

d2-d1

## Time difference of 2844 days

as.duration(d2 - d1)

## [1] "245721600s (~7.79 years)"